This new mini-series highlights the fascinating and marvelous ecology of grassland bird nesting, written by Madison Audubon education director Carolyn Byers. Click here for all Into the Nest posts.

Grassland bird nests are just about my favorite things ever. They’re perfect little secrets hiding in the foliage, holding precious babes. I love the way they are often fairly similar, but have subtle differences that let you identify who built them. (Sparrows are my favorite group of birds, which might explain why I love small brown things that look alike!) Nest searching is tricky business too -- and it feels like an incredible accomplishment when you find one.

My first official nest discovery was of a saltmarsh sparrow back in 2008. We had been searching for days, and I was beginning to think they were impossible to find. After finding the first one and getting a good search image, we found many more.

Photo provided by Carolyn Byers

Important Side-Note:

I want to take a moment to emphasize how important it is to respect bird nests. We will be sharing a lot of photos and videos of nests throughout the summer, most of which were taken from within a foot of the nest. Scientists have very strict rules about how to behave around a nest, how frequently we’re able to visit a nest, and how to treat the vegetation surrounding each nest. These rules protect the chicks and to try to prevent our presence from attracting predators to the nest. Please, please, please: if you find a nest, keep your distance, and only observe it in a way that doesn’t disrupt the parents. If the parents fly away from you when you approach the nest, you’re too close! Thank you for respecting our birds and keeping them safe during their most vulnerable time- when they’re in the nest.

If you’re interested in reading more about how we found nests during my thesis research or how we kept our nests as safe as possible, you can find more information at my website.

An eastern meadowlark gathers materials to do some housework. Photo by Matthew Paulson

Back to the story:

Nest site selection and nest building are ritualized behaviors that help to solidify pair bonds. Each species has their own special way of going about this. In some species like sedge wrens and northern harriers, both the male and female work to build a nest. In other species, the female alone builds the nest.

Where a nest is placed on the landscape is very important, and could make the difference between success and failure for the nest. Often when you look out at a grassland, you see the plants rippling in the breeze, feel the cool wind on your face, and think it’s a pretty ideal place for a hike. Under the grass can be a different story though. Next time you’re out in the prairie, lay or crouch down until you’re beneath the canopy of the grass. On a warm day, it can be stifling down there! Grassland bird nests are placed so that the nest is shaded or has some air movement around it to prevent chicks from overheating. Those protective grass clumps also provide shelter from intense spring storms. This small pocket of more favorable habitat is called a microclimate.

A thriving tallgrass prairie at MAS Faville Grove Sanctuary hosts all sorts of secretive birds. Photo by Brenna Marsicek

Birds have very few nest-building tools at their disposal: for the most part it’s just beaks and feet. One of my favorite projects to do with kids is to have them build their own bird nests. We collect dried grasses and other plants, sit on the ground, and try to weave it into a nest. All of them begin the project thinking it will be an easy task, but are dismayed by the end of it. None of their creations look like the tightly-woven masterpieces that birds produce. When I mention that if they were birds, they wouldn't have hands, the kids are even more impressed by the difficulty of the task.

To respect and protect our birds, we did not set video cameras on nests until after they were on eggs. The internet provides though! Here is a video of an American robin adding the layer of mud to her nest. While robins are not grassland obligate birds, they do nest there. You can see her carrying mud with her beak, using her whole body to shape the nest cup, and using her beak to make final adjustments. She will eventually line the mud cup with fine grasses, and other soft fluffy things.

The red-winged blackbird is another non-obligate that nests in grasslands. Here is a video of a female red-wing weaving grasses around standing vegetation to build her nest. If you’ve never looked closely at a female red-wing before, take a second glance here. I particularly love the peachy color on her face and breast.

Now, let's go deeper into the nest:

Drawing by Carolyn Byers

Northern Harrier

Harriers can place their nests in many different habitats (uplands, wetlands, and everything in between) but they are always found in a clump of dense vegetation. Both the male and female gather nesting material and bring it to the nest site. The female does the bulk of the work gathering material and building the nest.

Photo by Carolyn Byers

Northern harrier nests are built on a small platform of thick vegetation (cattails and small tree branches). The nest itself is composed of finer plant material (grasses, rushes, and sedges, Fleskes 1992). Nests can be 2-18 in high, are 15-30 in wide, with a nest cup diameter of about 8-9 in (Harrison 1975).

Eastern Meadowlark

Photo by Carolyn Byers

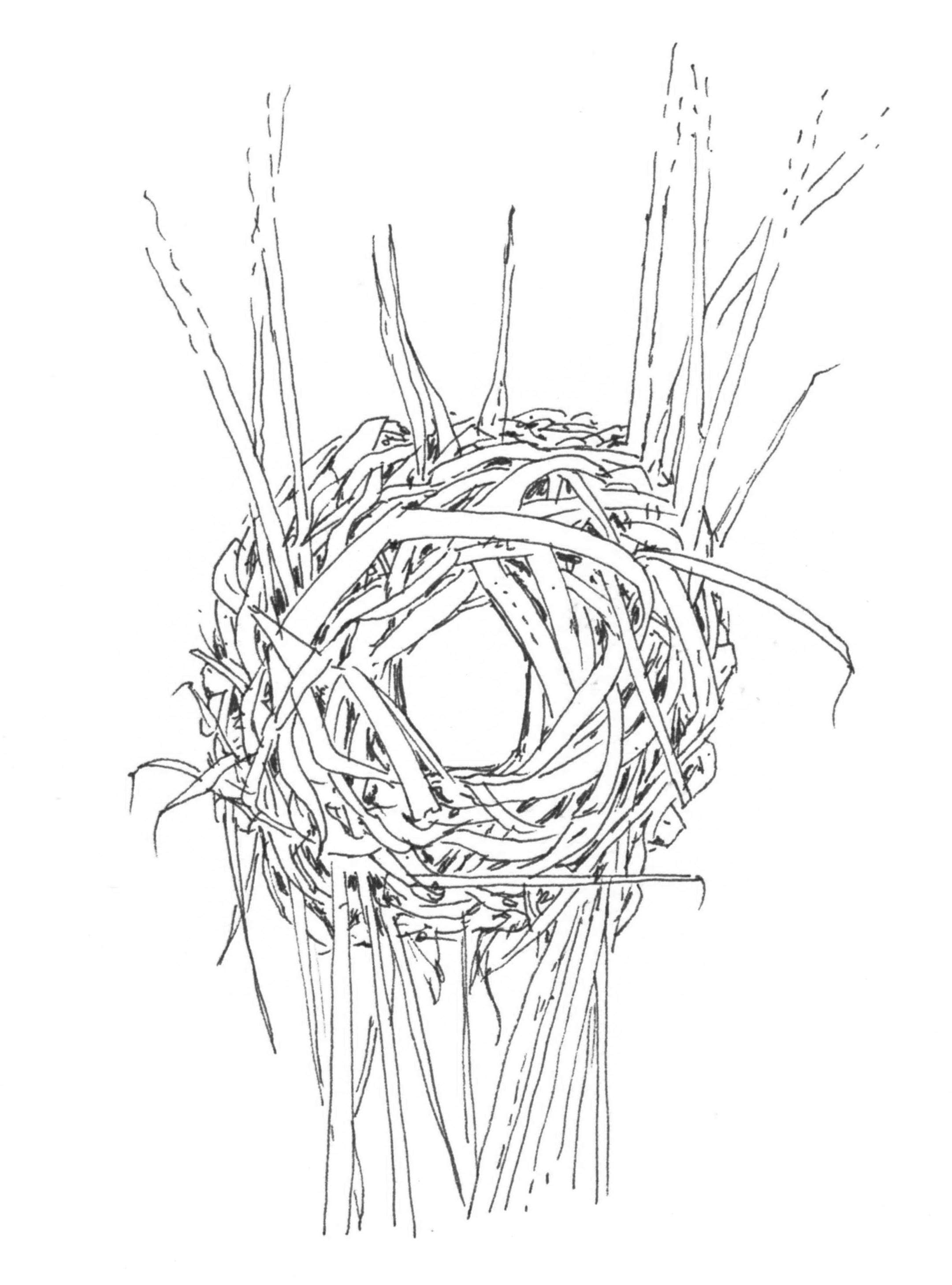

Drawing by Carolyn Byers

The female gathers all material and constructs nests (Nice 1965). Their first nest of the season is usually built in about six days, but subsequent nests are finished in only four days (Jaster et al 2012). Meadowlarks select nest sites with deep litter layer and place their nest under a clump of thick grasses.

Eastern meadowlark nests are built using coarse dried grasses and forbes. They weave these materials around the standing vegetation near the nest. Nests usually have a domed roof and the standing grasses surrounding the nest arch over the nest too. Sometimes there is a visible runway through the litter layer leading to the nest. Nests are 6.5 inches in diameter, 7 in tall. The opening is often about 4 in in diameter, and is taller than it is wide.

Henslow’s Sparrow

Photo by Carolyn Byers

Drawing by Carolyn Byers

Not much is known about how they choose where exactly to place their nest. We do know that they always hide their nest deep in the litter layer, and often at the base of a thick clump of grass which create a canopy overhead. Nests can be placed directly on the ground, or about 2-3 inches off of the ground, suspended by the litter layer. We think females are responsible for building the nests, but more research needs to be done on this (Hyde 1939).

Henslow’s sparrow nests are made with thick grasses and lined with thinner grassess or animal hair. The nest cup is typically 3 in wide and 2 in tall, and the walls are about half an inch thick.

Grasshopper sparrow:

Generally build their nests under vegetation that arches over the nest. The female builds the nest in only 2-3 days (Vickery, 1996). Nests are placed in a small depression in the ground so that the lip of the nest is level with the ground. They usually have a small half-dome over the back of the nest.

Drawing by Carolyn Byers

Photo by Carolyn Byers

Grasshopper sparrow nest cup and dome is made with thick grasses and woven into the surrounding vegetation. The nest is lined with fine grasses and sometimes animal hair. The nest is 4.5 - 5.5 in in diameter and a bit more than 2 in tall. The inside of the nest is 2-3 in wide and 1.25 in deep. (Harrison 1978).

Sedge wren:

Photo by Carolyn Byers

Drawing by Carolyn Byers

Sedge wrens are not grassland obligates, but they are really cool birds that nest in grasslands. Males build several “dummy nests”, which are just the outer shell of a nest. The female will then choose which one she likes best and finish lining the nest. The nest is woven around the standing vegetation, and is often about knee-height in grasslands. As the grasses grow throughout the season, nests get higher!

Sedge wren nests are made of thicker dried grasses with a lining of fine grasses, feathers, fur, and soft plant material (Harrison 1978). Nests are about softball sized: are taller than they are wide, and have an opening about the size of a quarter.

If you were a grassland bird, what would your nest look like?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Dickcissels are a beautiful, migratory grassland bird that benefits from the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

This summer, to celebrate Year of the Birdand 100 years of bird conservation under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, we’ll be posting regular articles about grassland bird nesting ecology. My M.S. thesis focused on grassland bird nesting ecology, and I’m excited to share my knowledge—and stories from the field- with you! We’ll go into the nest to learn about chick behavior, adult sleep habits, feeding and fledging. We’ll discuss predation and learn about how adult birds respond to different predators. You’ll get to see beautiful photos of nests, eggs, and chicks, as well as video footage straight from the nest! Best of all, the next time you’re out hiking in your favorite Wisconsin prairie, you’ll feel a bit closer to the birds you love.

If you’re interested in reading more and can’t wait for the next post, you can read more about my thesis work here.

Stay tuned for our next edition of Into the Nest, coming soon!

Written by Carolyn Byers, Madison Audubon education director

Cover photo by Carolyn Byers

Fleskes, J. P. 1992. Record of a Redhead, Aythya americana, laying eggs in a Northern Harrier, Circus cyaneus, nest. Can. Field-Nat. no. 106:263-264.

Harrison, C. J. O. 1978. A Field Guide to the nests, eggs and nestlings of North American birds. Toronto: Collins.

Hyde, A. S. 1939. The life history of Henslow's Sparrow: Passerherbulus henslowi (Audubon). Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Misc. Publ.

Jaster, L. A., W. E. Jensen, and W. E. Lanyon (2012). Eastern Meadowlark (Sturnella magna), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Nice, M. M. 1965. Displays and songs of a hand-raised eastern Meadowlark. Living Bird no. 4:161-172.

Vickery, P. D. (1996). Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.239