This series highlights the fascinating and marvelous ecology of grassland bird nesting, written by Madison Audubon education director Carolyn Byers. Click here for all of the Into the Nest posts.

While incubating eggs looks pretty boring, it seems easy enough. Stay quiet and hidden. Don’t attract predators to the nest. Keep the eggs at an ideal temperature and rotate them frequently. All of that changes as soon as there are chicks in the nest.

The length of time eggs must incubate depends largely on the species of bird that they belong to. Birds with precocial young (mobile and self-feeding after hatching) typically have a longer incubation period, because their chicks need to do a lot of growing before they’re ready to hatch. Upland sandpipers incubate their eggs for 21-27 days before hatching (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

This precocial wild turkey chick is only seconds old. It’s feathers still need to dry out! Within minutes, it is a little walking fluff-ball- ready to leave the nest and follow mom to food. Photo by Carolyn Byers

Birds with altricial young (born blind and helpless) have a shorter incubation period. The chicks can continue growing while they remain in the nest, and so hatch much earlier. Grasshopper, savannah, and Henslow’s sparrow incubate for 11-13 days, depending on the species. Bobolink incubate for 10-13 days, and dickcissel for 12-13 (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

These altricial red-winged blackbird chicks are helpless and totally reliant on their parents. They are just minutes old now, and will remain in the nest receiving care for another 11-14 days. Photo by Carolyn Byers

In some species, chicks and parents begin communicating even before eggshells are breached. Chicks will peep while still in the shell, and listen to the sounds their siblings and parents make. These whisperings help precocial chicks hatch at the same time: the noises made by chicks closer to hatching hurry the development of younger chicks (Brua 2002).

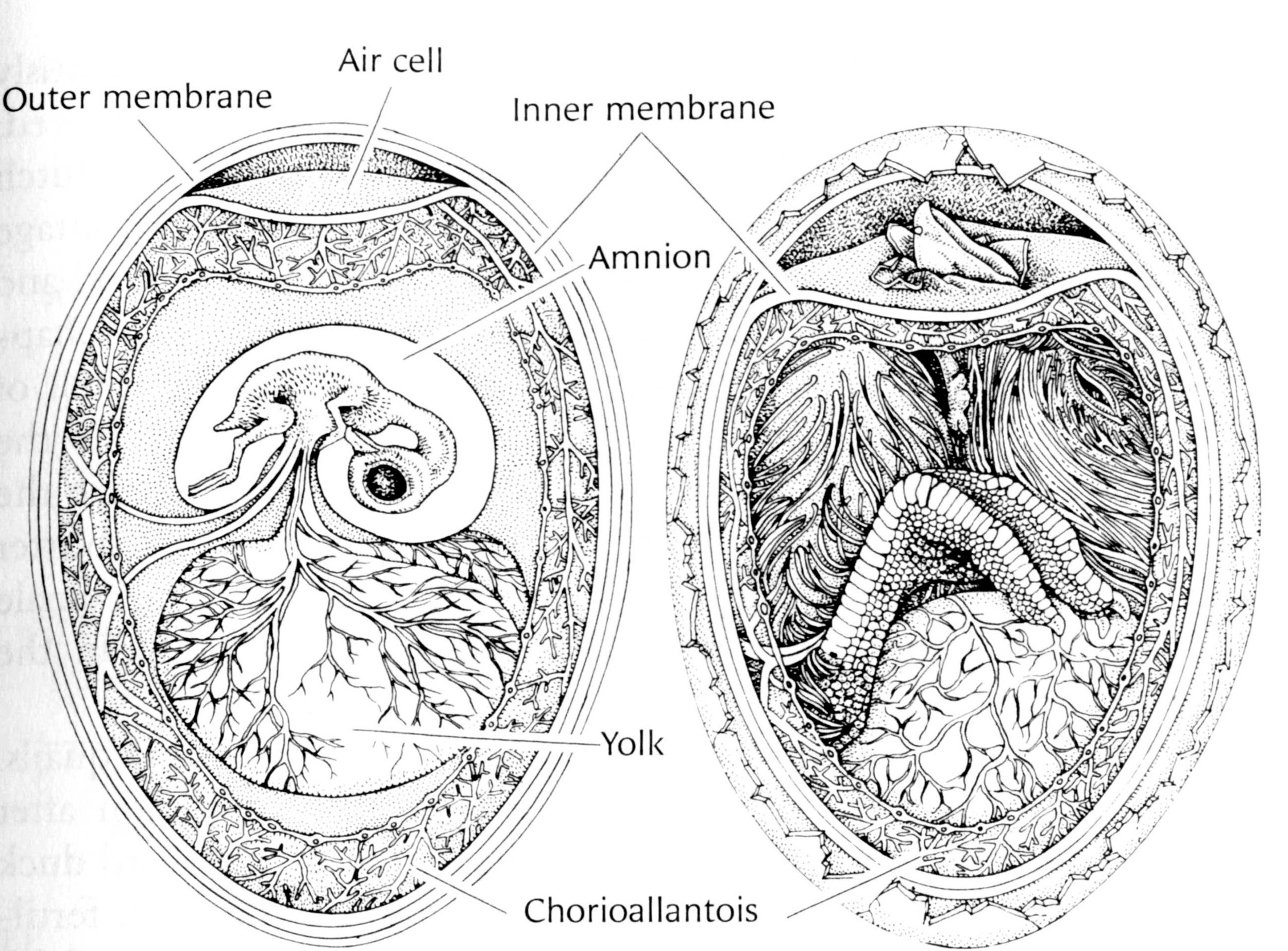

Hatching itself is a more complicated activity than it seems at first glance. A lot happens before the chick even breaks the shell. The chicks begin with their head at the blunt end of the shell and their ankles at the pointy end. They take their first breath of air by puncturing the air chamber between the shell and inner membrane.

Shortly before it hatches, a chick uses its beak to break into the inner air chamber, taking its first breath of air. Image citation: Gill 2007, Figure 15-22, page 461.

The chick will then peck weakly at the shell while rotating counterclockwise, creating small fractures in the shell. It takes about two days of this pecking, but the chick will eventually break through to the outside world. The shell often splits into two neat halves that the parents remove from the nest or eat.

These wild turkey eggs are beautiful examples of neatly split shells. Photo by Carolyn Byers.

Removing the shells keep the nest clean, which can help prevent predators from finding it. Ingesting the eggshells provides the added bonus of returning precious calcium to the female.

For the full hatching story, including the incredible details of chicks communicating while still in the egg, check out this National Audubon article The Art of Hatching- Explained.

A hatching saltmarsh sparrow. Caption: A saltmarsh sparrow is the first to hatch in its clutch. Photo by Carolyn Byers

NEST CAMERA FOOTAGE

We have another video to share this week! Remember, enjoy these videos for what they are: really rare footage of grassland bird nests -- but not necessarily the most beautiful footage you’ve ever seen. Hopefully what we’ll be showing you will be so cool that you won’t even notice the grainy images!

This meadowlark nest began with three eggs, the smallest of which is a brown-headed cowbird.

0:22 The female peeks at her eggs. A small piece of eggshell flies off of an egg, which the female eats. She may be eating more shell fragments as she peeks around at her feet.

0:36 She returns to shading her nest and gular fluttering, so it must be a hot day down in the grass.

0:38 You can see the hatching egg is cracked at the top, and the large crack in the eggshell allows us to see the chick moving within the egg!

0:50: Our little chick hatches, and the female helps remove the chick from the eggshell, which she removes from the nest.

1:20 The female returns with the eggshell (it's unclear why: perhaps she intended to drop it elsewhere and changed her mind? perhaps she just got startled earlier and quickly took off to evade danger? there are lots of possibilities). She eats the eggshell, keeping her nest clean and consuming the much-needed calcium.

1:43 She settles back into the nest, tending her newborn before sitting lightly back on the remaining eggs and the blind, naked hatchling.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Dickcissels are a beautiful, migratory grassland bird that benefits from the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

This summer, to celebrate Year of the Bird and 100 years of bird conservation under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, we’ll be posting regular articles about grassland bird nesting ecology. My M.S. thesis focused on grassland bird nesting ecology, and I’m excited to share my knowledge—and stories from the field- with you! We’ll go into the nest to learn about chick behavior, adult sleep habits, feeding and fledging. We’ll discuss predation and learn about how adult birds respond to different predators. You’ll get to see beautiful photos of nests, eggs, and chicks, as well as video footage straight from the nest! Best of all, the next time you’re out hiking in your favorite Wisconsin prairie, you’ll feel a bit closer to the birds you love.

If you’re interested in reading more and can’t wait for the next post, you can read more about my thesis work here.

Stay tuned for our next edition of Into the Nest, coming soon!

Written by Carolyn Byers, Madison Audubon education director

Video credit:

Nest footage was generously provided by the U.S. Geological Survey, Wisconsin Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, Madison, WI. Check out their website to learn more!

Works Cited:

Brua, R. B. 2002. Parent-embryo interactions. Avian Incubation, pp. 88-99 (D.C. Deeming, Ed.). Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Ehrlich, P.R., D. S. Dobkin, D. Wheye. 1988. The Birder’s Handbook. A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds. Simon and Schuster, Fireside. New York, New York.