Bird distributions are not random. Across the state, one notices that loons are a distinctly northern Wisconsin species, or that yellow-bellied sapsuckers occur over the northern half of the state, while also extending into western Wisconsin’s Driftless Area. Perhaps even locally, one notices an abundance of Canada Geese breeding around urban ponds, where park lawns and predator-free expanses make happy geese.

Color codes for breeding status.

Of peculiar interest to me, at Faville Grove Sanctuary, is the presence and absence of certain bird species. Today, we will observe the biogeography of certain bird species in Wisconsin, based on maps pulled from eBird data on the second Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas. To the right, you’ll see the different categories of breeding, based on quantitative observations gathered during Wisconsin’s recently completed five year long Breeding Bird Atlas.

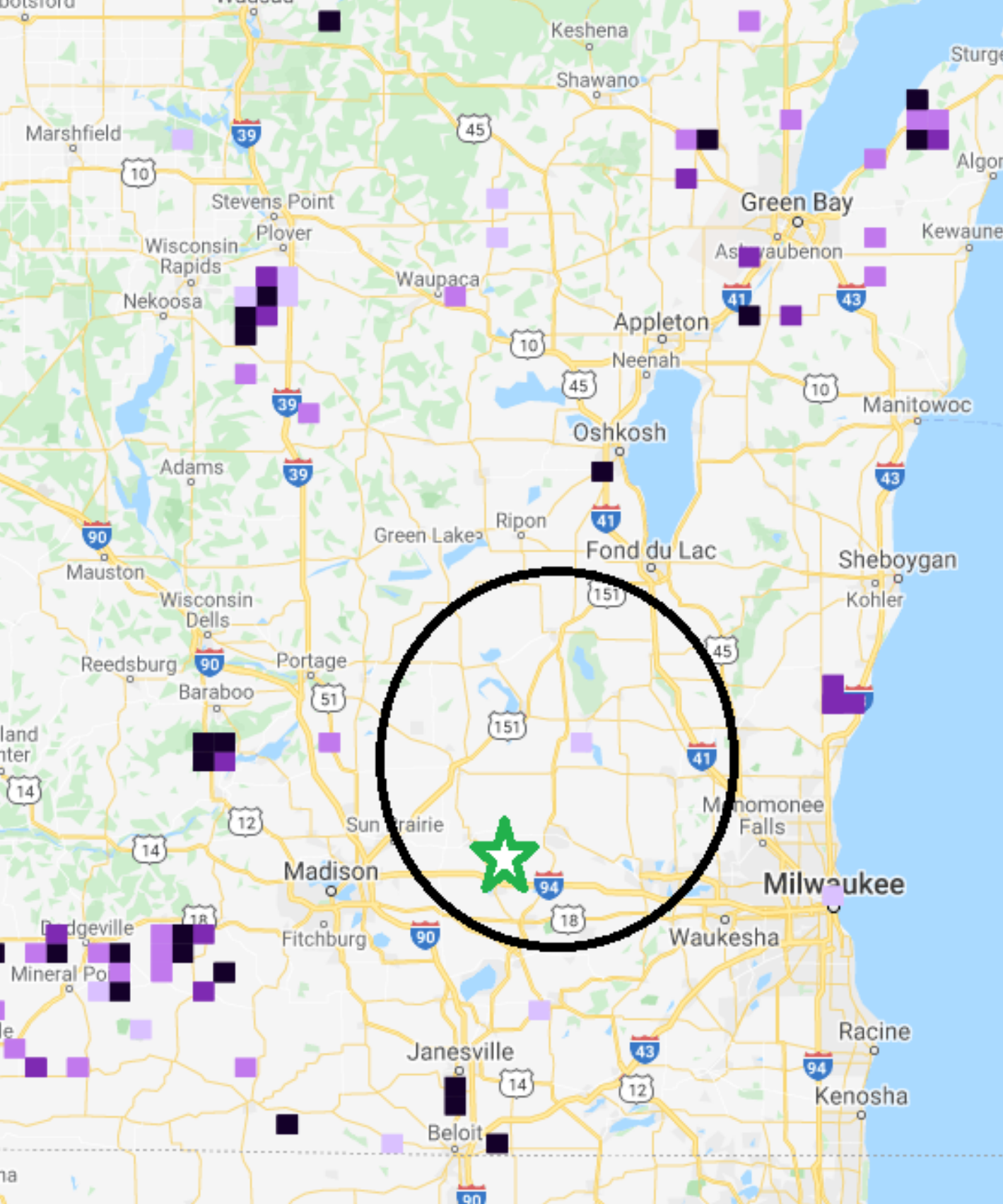

The striking feature of many of the maps that follow is the absence of breeding birds in the Faville Grove Area. From roughly Lake Koshkonong to south, Madison to the west, Horicon Marsh to the north, and the Kettle Moraine to the east, one notices distinct range gaps in many of these bird species. The absence of certain species in this region speaks to the necessity of a landscape-scale habitat project, and the presence of many of these birds at Faville Grove is a testament to the habitat restoration conducted here.

A fun game is to try and guess the species based on the map.

First, we will analyze the upland sandpiper. Formerly abundant at Faville Grove, the bird used to nest with up to one pair every 1.5 acres, though the birds have not been seen in decades. Art Hawkins, one of Aldo Leopold’s graduate students, published an important paper on the ecology of the Upland Sandpiper at Faville Grove.

The bird occurs south, west, east, and north of Faville Grove, though in very small numbers. South of Baraboo you can see a block of confirmations from the Sauk Prairie Recreation Area, which includes large acres of new prairie restorations. With new land acquisitions at Faville Grove forming large contiguous blocks of prairie, we eagerly await a possible return of the upland sandpiper.

Upland sandpiper, photo by Vitalii Khustochka, FCC

Upland Sandpiper breeding range in southern Wisconsin, conspicuously absent from the circled area. Star indicates Faville Grove Sanctuary

The short-eared owl was a common breeding species at Faville Grove up until Aldo Leopold’s time in the 1930’s and 40’s. The bird has returned with increasing grassland acreage, overwintering on a diet of meadow voles from the prairie. There is potential for breeding pairs with expanded contiguous habitat.

Short-eared owl, photo by Mick Thompson

The light purple block west of the I-94 marker is the atlas block that contains Faville Grove Sanctuary

A charismatic and bold bird, the red-headed woodpecker is a relatively common breeder in southern Wisconsin, though remains uncommon in the Faville Grove region. Oak trees and dead snags are critical to keep this species over summer, and a breeding pair has occupied this exact habitat at Hope Lake Bog (an outlying Madison Audubon property) for a number of years. Consistent sightings in the savanna of the Lake Mills Ledge indicate that the canopy thinning has improved habitat for this species.

Red-headed woodpeckers, photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

Red-headed woodpecker breeding locations.

A unique warbler with a warm buzzy song, the blue-winged warbler has been expanding northward in Wisconsin since the turn of the twentieth century. Between the first and second Breeding Bird Atlas, breeding pairs have moved even further north into the northwestern and northeastern parts of the state. Yet, the bird is strikingly absent from the Faville Grove Area. One pair was confirmed during the Atlas at the Waterloo Wildlife Area, to the north, where I have seen and heard dozens of the birds during migration. Nesting in shrubby areas and along forest edge, why the birds remain absent from Faville Grove remains a mystery.

Blue-winged warbler, photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

Breeding map for blue-winged warblers in southeastern Wisconsin.

A declining forest bird, the ovenbird lacks necessary habitat at Faville Grove. A ground nester, the ovenbird needs extensive forest tracts. From the map, we can almost identify the entire Kettle Moraine from southwest to northeast. It seems that outside of the Kettle Moraine, little suitable habitat exists. This is a common plight of many forest birds—the southeast glacial plains ecological landscape is about 4.9 million acres, with almost 3 million acres in agriculture. A mere 392,000 acres of the entire landscape is upland forest, and the only large blocks of forest are located in the Kettle Moraine, where you can also find ovenbirds.

Ovenbird, photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

Breeding map for ovenbirds in southeastern Wisconsin.

Found in young forests and shrublands, the mourning warbler occurs for the most part north of Faville Grove, but does breed in the Southern Kettle Moraine State Forest. Savanna restorations may be important breeding areas for this bird, though the overall extensive forest cover of northern Wisconsin is preferred.

Mourning warbler, photo by Tom Benson

Breeding map for mourning warblers in southeastern Wisconsin.

Here, we see a grassland species with an affinity for forb-rich prairies and high diversity. Faville Grove’s high diversity prairie restorations should provide excellent habitat for the grasshopper sparrow, and one singing bird this past summer could be an indication of a bright future at Faville Grove. Breeding pairs in this area would be an important population boost for the region.

Grasshopper sparrow, photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

Breeding map for grasshopper sparrows in southeastern Wisconsin.

Finally, we can locate Faville Grove’s block precisely on this map, where a black square west of the I-94 marker confirms the breeding of Henslow’s sparrows at Faville Grove. Unburned prairie seems a necessity for the Henslow’s sparrow, and a shifting patchwork of burns has provided excellent habitat for an increasing population of this state-threatened bird at Faville Grove.

Henslow’s sparrow, photo by JanetandPhil, FCC

Breeding map for Henslow’s sparrow in southeastern Wisconsin.

It could be that the geographic gap in species’ ranges is an artifact of the sampling—located between high population centers in Madison and Milwaukee, the gap apparent in many ranges could just lack sufficient birding. However, the map below shows many areas between Madison and Milwaukee with over 100 checklists, and an overall good coverage of the entirety of southeast Wisconsin.

Map of sampling effort in southeastern Wisconsin.

A confluence of factors merges to produce these range gaps in many species. As stated earlier, only 8% of the southeast glacial plains is upland forest. Of the entire landscape, only 4% is publicly owned. Small slivers of habitat tend to hold fewer birds than large blocks. Thus, on a landscape wanting for many bird species, a landscape-scale habitat restoration project like Faville Grove can fill the gap.

Written by Drew Harry, Faville Grove Sanctuary land steward