The wood thrush, found in forest interior habitat, is a charismatic and captivating forest bird. Mornings met with a wood thrush’s cheery and mystical song make any birder feel familiar in that forested environment. With an impressive vocal repertoire, from its unforgettable “ee-o-lay” to its more obscure pit volleys, which are a sharp series of notes—when a wood thrush is in a woods and it’s singing, it’s unmistakable.

Over the past 50 years wood thrushes have experienced significant declines of at least 60% of their population. Some research shows that wood thrushes overwintering in drier Mexican forest fared worse on breeding grounds, due to the droughty conditions and apparent lack of food availability. When those birds returned to North America to breed, they were in rough shape and laid fewer eggs or couldn’t care for the eggs they did lay. While destruction and fragmentation of forests in Central America certainly doesn’t help wood thrushes, it’s been found recently that fragmentation in North America might be the leading cause of population declines. Wood thrushes need large mature forest in order to breed, while constant disturbance in these forests may not benefit wood thrushes.

The oak and hickory woods at Faville Grove Sanctuary. Photo by Madison Audubon.

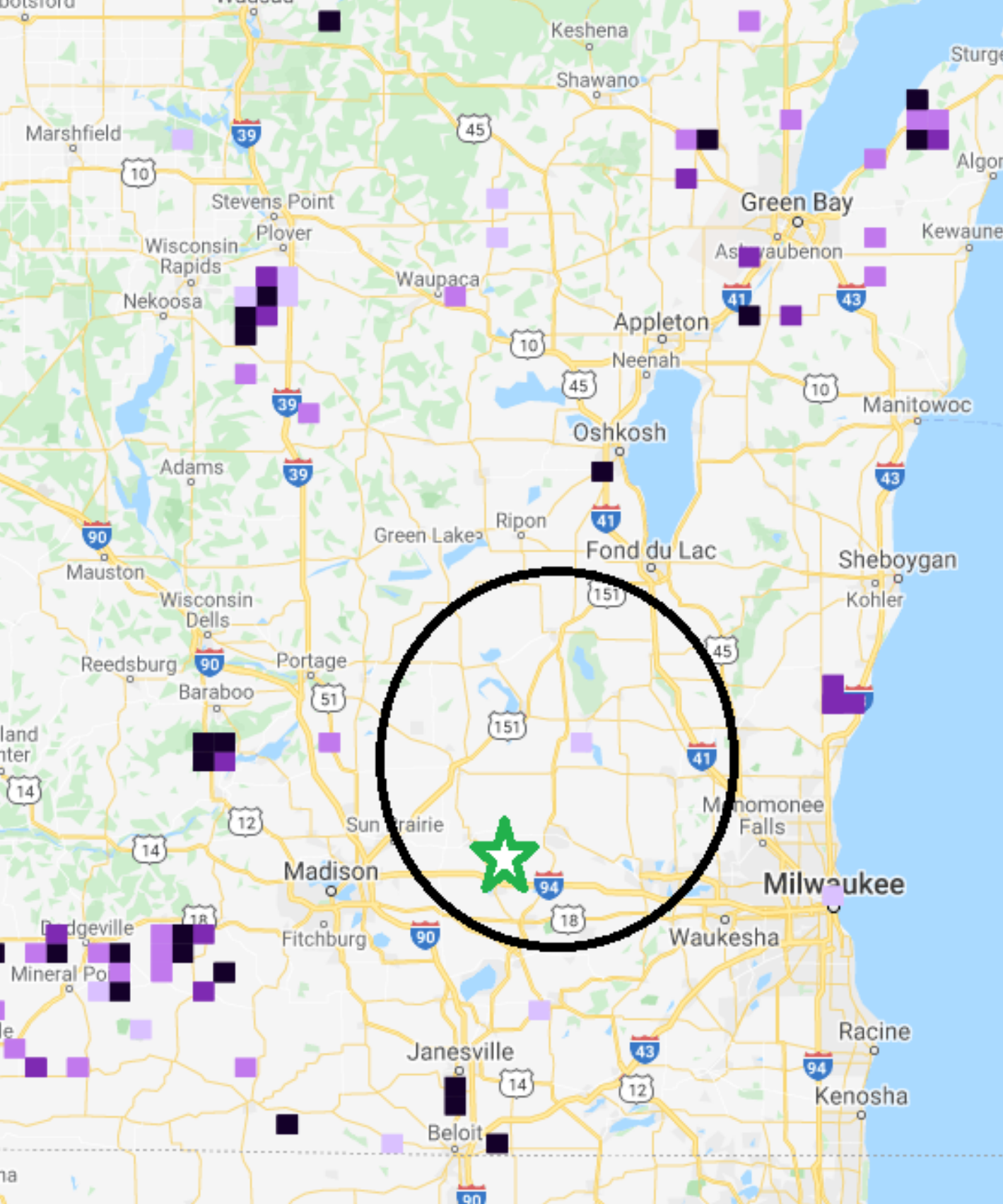

At Faville Grove, wood thrushes are uncommon in our mostly grassland landscape. However, nearby oak woodlands, lowland forests along the Crawfish River, and certain Tamarack swamps may hold a few birds. We’ve been hearing them more frequently with the interns in the past couple of weeks. Research shows that post-fledgling birds prefer to hang out in dense shrub thickets on the edge of forested habitat, likely for protection from predators and increasing availability of fruits and invertebrates. That post-fledgling movement may explain why we’ve been hearing them more recently around some grassland and shrubland areas. You should look and listen for this bird near larger forested tracks at Faville Grove.

Written by Drew Harry, Faville Grove Sanctuary land steward

Cover photo by Kelly Colgan Azar / Flickr Creative Commons